ECB meeting 7 September 2017, what to expect:

In late June at the ECB Forum in Sintra, the ECB Chairman Mario Draghi remarked that “all the signs now point to a strengthening and broadening recovery in the euro area.” The market took this as a sign of the impending end to QE and the EUR began a rally from 112 to 119 and change. The ECB was quick to moderate the message soon after Draghi’s remarks. More recently the ECB has expressed concerns about the strength of the EUR, and at Jackson Hole this week, Draghi was careful not to telegraph any intentions as to the future trajectory of QE or interest rates.

On Sep 7 next week, the ECB will meet to decide on monetary policy. It is clear that the Eurozone economy has stabilized and is in the middle of a cyclical upturn, led mostly by Germany. However, growth rates are not equal, nor are labour markets. The variation of unemployment in the Eurozone ranges from 3.8% in Germany to 21.7% in Greece with Italy at 11.1% and the Euro area average at 9.5%. Greece and Ireland have negative rates of inflation with the region average at 1.4% while economic powerhouse Germany manages only 1.67%.

Given the ECB’s mandate of 2% target inflation, it is clear that policy has not achieved its aims. Not only that, it exposes the fact that policy is unable to address the varying growth, unemployment and inflation rates of the member countries. The single currency may have brought about convergence in interest rates up until 2008 but it has if anything exacerbated divergences in factor prices in the Eurozone, as conventional economics predicts it should if member countries have different factor productivity, which they do.

Not only has policy not achieved its aims but the current QE will run into technical difficulties. By buying bonds pro rata to the capital key, the ECB’s accommodation is strongest in Germany and weakest in the periphery. The limitations on how much of each issue the ECB (and by extension the national central banks) can buy and the issuance of bunds means that the ECB will not be able to maintain its volume of bund purchases much longer. Since it has to buy according to the capital key, this limits how much it can buy of peripheral bonds. The ECB may have to taper its asset purchases simply because it runs out of bunds to buy.

What the ECB needs to do is to find a way of buying or enabling the buying of, Eurozone bonds according to the needs of each economy, and not according to the capital key. Given how the rules are drawn up, and the opposition it faces from the Bundesbank, it will not be able to directly buy bonds. It will likely have to resort to a mechanism it first engaged in late 2011, the unconditional LTRO.

Why the original LTRO worked:

The national private commercial banks bought bonds which the ECB could not. As long as the bonds they bought were eligible collateral, and had a yield above zero, private commercial banks would have an incentive to buy them, since they could be financed effectively at 0% in the LTRO.

The original LTROs were not conditional on the size of banks’ loan books. Banks could buy as much of sovereign bonds as they liked with LTRO money. Under the later TLTROs, the size of their LTRO utilization was conditional on their loan books. If the banks could not or would not increase their loan books, they could not increase their LTRO participation. This is one reason why TLTRO take up (some 400 billion EUR) was much smaller than LTRO take up (which topped a trillion EUR).

The LTRO is ideal in encouraging private commercial banks to perform proxy-QE for the ECB, and would circumvent the capital key. Assuming that the single currency did not break up, banks would be incentivised to buy bonds of Italy, Spain and Portugal, where yields were highest, and not bonds of France and Germany where yields were tightest, and up to 10 year, negative. Assuming that there was some default risk and break up risk, at least the national private commercial banks of Italy, Spain and Portugal would buy their own respective national debt. If nothing else this would push also their current accounts further into surplus and narrow the spreads to French and German bonds.

If we believe that the ECB intends this route, then we also know that they are unlikely to raise interest rates since the LTROs require super cheap funding to work.

The September 7 ECB meeting is very much up in the air. The last 3 months have seen conflicting signals and some clumsy communications by the ECB. I believe that in the current environment, the ECB will do the following:

1. Hold interest rates at -0.4%.

2. Announce a tapering of bond purchases in the public and private markets.

3. Announce a resumption of unconditional LTRO up to a size of 1 trillion EUR over the next 12 months.

The consequences of this, based on lessons and parallels drawn from Dec 2011, could be:

1. Exert downward pressure on the EUR.

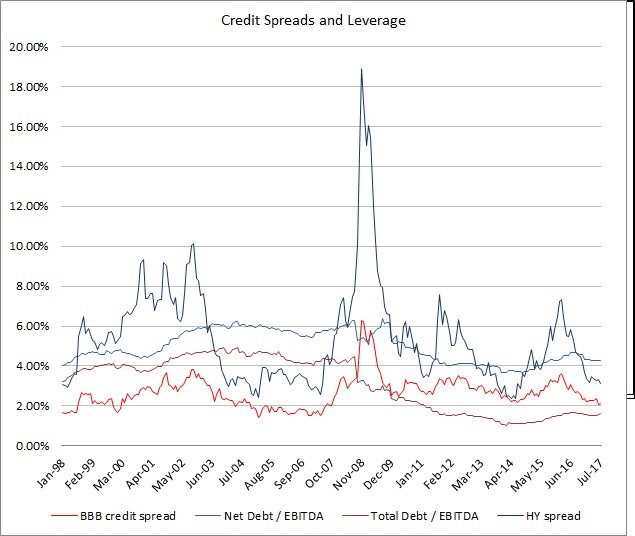

2. Bring convergence between peripheral rates and bunds.

3. Trigger a rally in EUR high yield.

4. Impact on equities not so certain.