Singapore Property Has Bottomed. Will Rise. Beware The Rebound.

The Singapore property market has been receding slowly since 2013. It has bottomed and will rise. There are a number of factors behind this.

The Singapore economy is stabilizing and will accelerate from this year onwards. No economy slides for multiple years without recovery. The Singapore economy is an uncommonly trade oriented economy with imports and exports together accounting for over 400% of GDP. International trade weakened from 2011 to 2016 as the world engaged in a Trade Cold War. In every trend there is a respite and international trade has rebounded. The impact on Singapore has been and will be positive. The oil sector is another significant component of the Singapore economy. Oil prices were 110 in late 2013 and have tracked lower till 2016. Since then they have stabilized providing some relief to the oil sector in Singapore. These two factors alone are sufficient to support the economy in the short term.

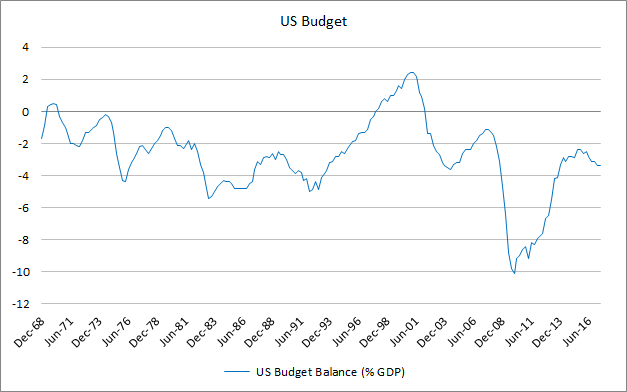

Interest rates (SIBOR) which rose sharply from across 2015 have now stalled. SIBOR is influenced by USD LIBOR and the SGD exchange rate, the latter being subject to central bank policy. The weakness of USD and the lack of inflation in the US has dampened the rate of ascent of interest rates. There is still a risk, however, that rates will climb. SIBOR was 0.4% in 2013/2014 and rose sharply to 1.25% in 2015. It then fell back to 0.88% in mid-2016. Since then it has risen slightly again, so this factor is not without its risks. More on this later.

Inventory build will start to weaken from 2018. Real estate is a very stationary and auto correlated industry. Low frequency of building and transaction data make planning and production slow to calibrate to demand and as a result the industry is prone to periods of over and under supply. The housing boom from 2005 – 2013 was prompted by undersupply but since then developers’ have over produced in expectation of extrapolated demand. As prices fell, developers cut back on production and the inventory build is now being eroded.

The expectation that Singapore real estate will appreciate is therefore built on sound, fundamental pillars. Demand and supply imbalances are being eroded. The cost of financing is low. The economy is in a recovery phase. Given the stationarity of real estate prices, one would argue that we are at the beginning of a 3 to 5 year upswing.

There are, however, risks to the investment thesis.

Property curbs remain in place. The limitations on household indebtedness and debt service are prudent measures which improve the stability of the banks and the housing market. Any relaxation of these measures might provide a short term boost to the property market but would contribute to future instability. Government policy may seek to moderate any increases in housing prices on social as well as economic fronts. If the situation in Hong Kong is a guide it demonstrates what can happen if house prices are allowed to rise without bound. Inequality of wealth and income in Hong Kong is acute and at risk of precipitating social discontent.

Housing as a source of wealth generation and accumulation may crowd out effort and enterprise. If people regard the provision of labour or engagement in enterprise as relatively inefficient generators of wealth compared with real estate investment, it may crowd out labour productivity and diversification of investment. The government may wish to discourage an over allocation of resources and focus to a single segment of the economy.

Interest rates are low. This may be counterintuitive but one should buy property when rates are high, and sell when they are low. This is perfectly intuitive when one replaces property with any ultra-long duration asset. An additional complication is that when interest rates are as low as they are, 1.4% for a floating rate SGD mortgage, 1.25% if you are a good customer, then debt service is very negatively convex. Consider that if interest rates were 5% and rose to 6%, the interest element of monthly payments would rise by a 20% whereas if rates rose from 1.25% to 2.00%, the interest element would rise by 60%. On a risk adjusted basis, the financing risk of such a long duration asset can be considerable. Even for those able to finance their purchase entirely in cash up front, the risk remains since if neighbours are weak holders, their transactions and indeed the valuations of potential buyers will impact the general valuations across the market.

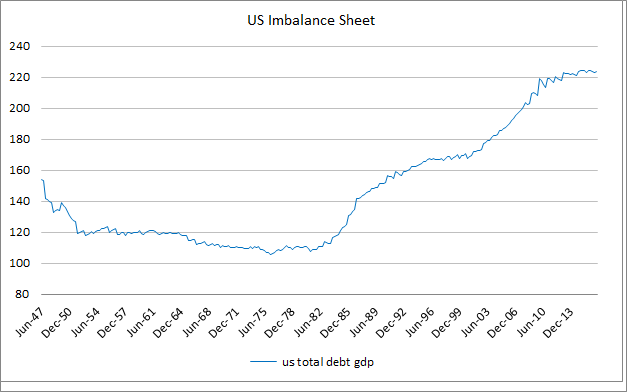

The Singapore economy is a volatile one. Whereas quarter on quarter growth of the US economy tends to range from 1% – 3%, the Singapore economy’s quarter on quarter growth ranges between 0% – 10%. The volatility of the Singapore economy comes from a number of sources. Lack of domestic demand and a dependence on international trade means that the implied leverage of the economy is high. Also, international trade is less within the control of economic policy than a more domestically based economy. The government’s control variable is the SGD exchange rate and not interest rates, making interest rates a state variable which is not under the control of policy. At some point the real estate debt service of the nation may become a complication to economic policy.

Another source of leverage is the substantial size of the financial sector in the Singapore economy, some 13% of GDP. For comparison, financial services are less than 8.5% of the US economy, and less than 7.5% of the UK economy. The high leverage of the financial services industry pulls up the leverage of the Singapore economy making it sensitive to credit conditions and interest rates. This adds to the volatility of the economy as a whole.

Regional competition is another risk to Singapore. Singapore’s rise has been rapid as it moved from third world to first, but having made this transition it faces first world problems including inequality, accelerating aspirations relative to potential, and a natural slowdown as the economy reaches potential and achieves terminal velocity. The property market gains of the 1970s to 2000s were compensation for frontier to emerging market risk, plus an economy catching up to developed market status. Singapore is now a developed market facing the dearth of ideas and demographic and developmental speed limits of any developed market. All around it the region is catching up and offering new opportunities for development and growth.

Finally, a risk that is generic to real estate and not to Singapore alone: real estate is not liquid. To compensate for this, returns should be high. Illiquid investments are best undertaken in countries with a long history of stability, where institutions have persisted across multiple and diverse generations of government, where rule of law is immutable and durable and has persisted across multiple and diverse generations of government. Otherwise, liquidity, transferability, portability are qualities which could become valuable, qualities which cannot be found in real estate.